Mechanical Engineering Training in New Zealand – Learn by Doing

Mechanical engineering training in New Zealand is often discussed as a practical way to understand how engineering concepts are applied in real working environments. This article offers an informative overview of training pathways available in the country, with an emphasis on learning by doing and developing hands-on technical skills. It explains how mechanical engineering programs are typically organized, what kinds of practical activities are commonly included, and how different study options may suit varied learning preferences. The content is intended to help readers gain a clearer picture of what mechanical engineering training in New Zealand can involve, without presenting guarantees about qualifications, certifications, or future career outcomes.

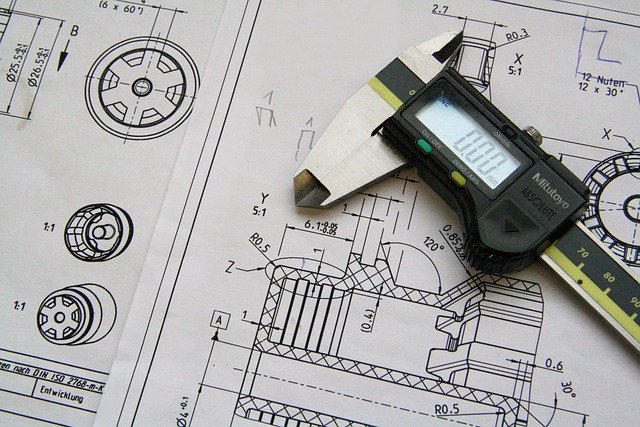

Mechanical engineering training in New Zealand is commonly framed around turning concepts into workable solutions, not only reading about them. Learners often encounter a blend of classroom fundamentals and supervised practical work, where measurements, materials, and tolerances matter. While the exact balance varies by provider and level, the overall emphasis is frequently on applying engineering thinking to real constraints such as time, safety, and manufacturability.

Why practical learning is common in New Zealand programs

Mechanical engineering training in New Zealand is often described as a practical learning approach because many engineering skills are easiest to develop through repeated application. Drafting a component, selecting a material, or planning a safe machining step involves judgement that grows with practice. In a New Zealand context, programmes may also reflect the needs of local industries such as manufacturing, energy, building services, and maintenance, where applied problem-solving is valued.

Practical learning can also support clearer feedback. When a design fails a fit check, a weld distorts, or a measurement is inconsistent, the learner gets immediate evidence of what worked and what did not. That loop can help connect maths and physics to day-to-day engineering decisions, without implying that a single method suits every student.

What “learning by doing” looks like in workshops and labs

Programs commonly emphasize learning by doing and hands on technical activities through workshop routines and lab-based exercises. Depending on the level, this might include basic machining principles, fitting and turning, using precision measuring tools, introductory welding processes, or assembling and testing mechanical systems. Safety and documentation are typically embedded, including risk controls, tool handling, and recording results in a consistent format.

Hands-on learning is not only about tools. Many courses use structured projects where learners interpret drawings, plan steps, and check results against specifications. In more advanced settings, practical activities may connect to computer-aided design, computer-aided manufacturing concepts, or instrumentation and testing. The aim is usually to build a habit of checking assumptions and working methodically, rather than relying on guesswork.

How training pathways are typically organised

The article explains how mechanical engineering training pathways are typically organized by level, specialisation, and the amount of supervised practice. A common structure starts with foundational studies that cover engineering mathematics, materials, drawing interpretation, and workshop safety. As learners progress, tasks may become more open-ended, integrating design choices, process selection, and quality checks.

Pathways can also be organised around the setting in which learning happens. Some routes are primarily campus-based, with scheduled labs and workshops. Others combine employment-based learning with formal study components. Assessment approaches can include practical demonstrations, project reports, and theory tests, with requirements differing between providers and qualifications.

Study options for different learning preferences

Different study options are outlined to reflect varied learning preferences, because mechanical engineering learners often differ in how they like to engage with technical content. Some prefer structured classroom teaching followed by supervised practical sessions. Others learn more effectively through project-based work where theory is introduced as it becomes necessary to solve a real design or maintenance problem.

Options may include full-time study, part-time study for those balancing other commitments, and blended formats that mix online learning for theory with on-site workshops for practical competencies. Work-integrated learning can appeal to learners who want frequent exposure to real equipment, workplace communication, and operational constraints, while campus-focused study can suit those who prefer a more controlled progression through topics.

What an overview can and cannot promise about outcomes

The content provides an informative overview without guaranteeing qualifications or career outcomes, because results depend on entry requirements, programme rules, assessment performance, and personal circumstances. Completing training may involve meeting attendance expectations, passing both theory and practical components, and demonstrating safe practice. Recognition of prior learning or credit transfer, where available, also depends on provider policies and evidence quality.

It is also worth separating “hands-on” from “easy.” Practical engineering tasks can be demanding, requiring careful measurement, patience, and the ability to revise work when results are not within tolerance. A realistic expectation is that training builds capability over time through repetition, feedback, and progressively more complex tasks, rather than through a single course or short experience.

Mechanical engineering training in New Zealand is often associated with practical instruction, but the specific pathway is usually a personal fit question: the right mix of theory depth, workshop exposure, and learning pace. Understanding how programmes structure hands-on work, how pathways progress, and what study formats exist can help learners set realistic expectations about workload and skill development while keeping outcomes grounded in what training can reasonably support.